{UAH} How Grenfell survivors came together - and how Britain failed them

How Grenfell survivors came together - and how Britain failed them

The strongest campaign group to emerge from the disaster is facing its most devastating challenge: government inaction. By Robert Booth

At sunset on a chill March evening beside Notting Hill Methodist church, survivors of the Grenfell Tower disaster gathered for a monthly ritual: a silent walk to remember the 72 people killed by a fire that roared up 20 storeys in 25 minutes, belching toxic smoke. As the flames raged through the night of 14 June 2017, families huddled and died together in their homes; some stayed on the phone to loved ones, who heard their final breaths. People scrambled over dead bodies to escape, and at least one person jumped.

As the group gathered, 21 months on, the atmosphere was muted and calm, but there was a current of pain as survivors and the bereaved greeted each other. Among them was Ed Daffarn, 56. He had been a punk in the 1980s, had moved into Grenfell in 2001, and beaten addiction to become a mental-health social worker. In the months before the fire, he had been writing a blog voicing the tenants' frustrations. In one chillingly prescient post, he had predicted that the landlord's failure to care for the tenants' safety or to listen to their needs would end in tragedy.

Next came Karim Mussilhy, 33, who was working as an Audi sales manager in Mayfair before the fire. His uncle, Hesham Rahman, had lived on the top floor of Grenfell Tower, and Mussilhy spent frantic days searching for him. After three weeks Hesham was presumed dead, and by the end of August his remains had been identified. Months later, once the building was stabilised, Mussilhy scaled 24 flights of narrow stairs, past sooty handprints of fleeing adults and children, to Hesham's flat. Inside, the total blackness of the walls and melted light fixtures confirmed to him the terror and helplessness his uncle must have felt. He recited Qur'anic verses, prayed and said sorry, even though it wasn't his fault.

The marchers set off at a prayerful pace, and the only sounds were shoes on tarmac and cars on the nearby Westway flyover. Police made the traffic wait at junctions, creating space for the Grenfell mourners, sod the inconvenience. Drivers waited. No one honked their horn.

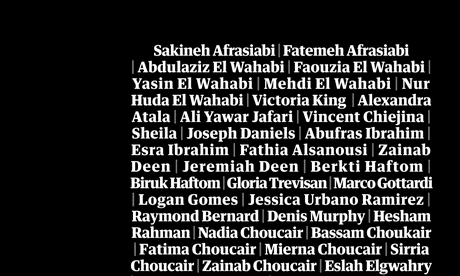

After about 90 minutes, the procession wound up beneath the Westway in a concrete undercroft covered with murals bearing slogans such as "blessed are they that mourn" and "convict RBKC [Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea] for corporate massacre". The tower, shrouded in white plastic, loomed like a totem. The marchers turned towards it for a minute's silence and the names of the dead were read out by those present. Among them present was Natasha Elcock, a mother of three, who escaped with her partner and six-year-old daughter only when the flames were roaring through her 11th-floor kitchen window.

Elcock, a supermarket manager, is now chair of Grenfell United (GU), the main group representing survivors and the bereaved. In the two years since the fire, this group has been shaped by its committee members – who include Daffarn and Mussihly – into something remarkable. It was one of dozens of support and campaign groups to emerge in the immediate aftermath of the fire, but has become the most enduring and influential. Its members now include most of the 305 survivors and hundreds more bereaved relatives.

While other groups, such as Justice 4 Grenfell, have tended to be more vocally political and have forged relations with trade unions, GU aims to be non-partisan. Its founding mandate called for "a strong, independent, united and dignified voice for the residents" to "keep the community together, to provide support to one another in rebuilding lives, to seek justice and accountability and to honour the memory of those who died". But they have been drawn towards bigger goals, including winning greater powers for England's 9.5m renting households, improving fire safety and ending prejudice against social-housing tenants. All the while, they are wrestling with their own grief and trauma.

In a way, they had no choice, because the fire at Grenfell exposed some of the gravest social problems facing Britain today. Deepening divides along race and wealth lines, and the seriousness of the housing crisis, were reflected in the fate of a single neglected council block.

Grenfell shattered Britain's image of itself as a houseproud nation. In Kensington and Chelsea, the country's richest borough, where billions of pounds in private investment had poured into new luxury housing, a few hundred thousand pounds had been cut from Grenfell's refurbishment budget, resulting in the use of cheaper, combustible cladding materials that burned like petrol. It was symptomatic of a national housing crisis in which more than 1 million renters suffer overcrowding; more than 300,000 homes stand empty and more than 2 million people live in homes so decrepit they are a serious health hazard.

In the aftermath of the fire, it turned out that tens of thousands of other residents in more than 400 residential tower blocks across England were living in flats wrapped in similar materials. Public officials were routinely signing off housing as safe based only on drawings and not site checks. Builders were bodging life-saving safety features, such as leaving out firebreaks in facades. The disaster also exposed an ugly seam of prejudice about residents of social housing.

Grenfell United is trying to tackle all this and more. By directing their anger into proposals for reform, a group of marginalised local authority tenants have penetrated a system that previously showed them only institutional indifference. They have reached the Downing Street cabinet room, where they have challenged the prime minister.

The group's commitment to closing the gap between these two distant worlds is not without personal risk. They have yoked their own recovery to achieving solutions to profound social problems. It is a courageous choice, because their own mental health and ability to restart their lives in part depends on success.

Now, as the two-year anniversary approaches, everything they have been fighting for hangs in the balance. Serious concerns remain over the effectiveness of the public inquiry into the disaster, delayed again last month, while hundreds of other tower blocks remain – by the government's own standards – unsafe.

Back under the Westway, Mussilhy addressed the crowd from the stage: "We fight every day; our own fights, our loved ones' fights, and we fight for the whole nation. That's the most important part of all. We will never get our loved ones back, but it is not too late for others. But our voices, yet, seem to be echoing into space. Nothing has changed after all this time, but yet everything has changed, for us at least."

This is the inside story of Grenfell United: a story of survival.

Ed Daffarn loved his 13th-floor flat in Grenfell. Along one wall he stacked hundreds of LPs: reggae, Bowie, the Clash and classical music from his late father's collection. In the corner he propped his cricket kit-bag. But in recent years he had come to loathe his landlord, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organisation (KCTMO), which managed the tower for the council. His frustration peaked during the two-year, £10m refurbishment, completed in 2016, during which the tower was wrapped in aluminium composite cladding. Daffarn had felt repeatedly fobbed off by the landlord. Promises to consult residents about works to reclad the tower, in part to improve its appearance to surrounding residents, were broken, and freedom of information requests for project minutes were refused. The leadership of Kensington and Chelsea, which owned the tower, took criticism personally and "couldn't see that they were public servants performing a public function" but behaved as if they were in a private members' club, he said.

Daffarn and Francis O'Connor, who lived on the neighbouring Lancaster West Estate, poured their efforts into dozens of carefully researched articles on their Grenfell Action Group blog, which was dedicated to charting indifference and neglect from their landlords. Seven months before the fire, Daffarn wrote: "It is a truly terrifying thought but … only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlord … and bring an end to the dangerous living conditions and neglect of health and safety legislation that they inflict upon their tenants and leaseholders." It warned that the tenants' management group's "sordid collusion" with the council is a "recipe for a future major disaster".

Normally about 200 people a month clicked on the blog, but in the hours after the fire, it recorded 3m hits, and Daffarn became known as the "prophet of Grenfell". "I can't explain it to you," Daffarn told me. "I'm not a religious person, but that blog wrote itself."

Ed Daffarn. Photograph: David Levene/The GuardianWhen the disaster he predicted came, on 14 June 2017, Daffarn was listening to late-night BBC London talk radio. He smelled burning, but thought it was just food, until Willie Thompson, a 62-year-old father of two who had lived in Grenfell for 20 years, telephoned him shortly after 1am and yelled at him to get out. When Daffarn opened his front door, billowing smoke filled the corridor. "Shit man, this isn't going to end well for me," he thought. Out in the hallway, he couldn't see, and couldn't breathe. He was convinced he had just three breaths left when a firefighter grabbed his leg, and led him to the fire escape. He ran for his life down the stairs and when he got out and looked up at the inferno. "I was wailing inside my soul," he told the public inquiry.

In the terrible chaos in the early hours of that Wednesday morning, stunned survivors found refuge where they could. Daffarn went to Rugby Portobello, a nearby sports club, one of several community centres that opened their doors in the middle of the night. One of Daffarn's neighbours, Shahin Sadafi, was also there. He had been in Kent at a business conference, but sped through the night back to London to rescue his mother from "a scene you only see in movies and war zones". Sadafi found her alive and safe, but was devastated by the chaos. At the time, the official death toll was six, but that did not tally with the 30 or more body bags he had seen with his own eyes that night. Even as the flames died down, there seemed to be no organisation for survivors. He wondered: "Are they trying to cover up the truth?"

"I nearly lost my mind," he said. "I started becoming so enraged. I said to Ed: 'We have got to find out what is going on. We have got to bring people together, find our neighbours.'" In the midst of fear and anger, he saw a purpose. It was "a motivating moment", he said.

The sports hall was hot and sweaty, with babies crying, but a handful of Grenfell residents started to gather themselves on that first day, and made lists of names and numbers of survivors who passed through. It became "a piece of sanity" amid the chaos of random donations flooding in, cash being handed out and journalists looking for stories.

"It was very obvious, at that stage, that nobody else was going to do anything for us," recalled Daffarn.

"We would say: 'Right guys, back here tomorrow at 9am. Let's meet and get some action going,'" Sadafi said.

On Thursday 15 June, when the extent of the death toll was becoming clearer, Sadafi and Daffarn tried to call a meeting to order. Some 55 people were in the sports hall where survivors had gathered after a sleepless night.

"The voices and the trauma were so large that we realised we weren't going to be able to facilitate a group ourselves," said Daffarn, who by now was feeling a sense of dread and angst at the extent of the abandonment by the authorities and in reaction to the trauma. "We felt we were having to find out for ourselves who was alive and who was dead," he said.

As the weekend approached, Daffarn was growing concerned that the community was scattering at a time when they needed to pull together. And then a group of pop stars showed up.

Marcus Mumford, the frontman of Mumford and Sons, and Adele, the Grammy-winning singer, had been quietly volunteering from the morning of the fire at Clement James church, another response centre. They wanted to do more, and came together with the singer Sam Smith, Will Champion, the drummer from Coldplay, and the rapper Dave to propose a charity concert. Daffarn didn't recognise Mumford, and by now had missed three night's sleep. He thought: "You think a rock star's going to help this?"

Daffarn and Sadafi were becoming aware that the community response to the disaster could easily turn violent. Kensington and Chelsea town hall had been stormed two days after the fire, and a group calling itself Movement for Justice By Any Means Necessary called for "a day of rage" the following week. The pair instinctively felt more violence was the wrong response to the traumatheir community had just suffered.

Plenty of people felt differently. Willie Thompson, who was involved with Daffarn in a residents' group called The Grenfell Compact, and had alerted his friend to the fire, was also at Rugby Portobello and was asking himself if they shouldn't have taken a more direct approach before the fire. "Eddie and the others, they like to sit down and talk and have meetings," he said. "I will accept that up to a point, and then I will start kicking doors. I would have been willing to be locked up for the cause."

Willie Thompson. Photograph: David Levene/The GuardianIn the days after the fire, Daffarn and Sadafi realised they badly needed someone to help them set up a group. A local intermediary introduced Oliver McTernan, a softly spoken Irish priest, who had worked for decades in conflict resolution in the Middle East, most recently in Tunisia, Egypt and Gaza, but had also been a parish priest in North Kensington. On 22 June, a week after the fire, McTernan helped call a meeting to try and agree a mandate for Grenfell United.

"We asked the simple question: 'What are your needs?'," recalled McTernan. "I was very struck by what the very first lad said: 'Dignity.'"

People weren't screaming for revenge, or demanding money. They talked instead about being strong, independent and unified. McTernan was impressed. The feeling was not that structures needed breaking; instead, the botched refurbishment and the neglectful response to the fire proved that structures needed to be built up.

And so the first formal meeting of Grenfell United took place on Saturday 24 June 2017. The minutes read: "Residents are not present as individuals. They must organise and they must establish a structure."

Mumford, who had continued to volunteer, helped secure GU an office and an assistant on the executive floor of his record label's south Kensington HQ. Rooms lined with gold discs where recording deals with Amy Winehouse and the Rolling Stones had once been signed were provided by David Joseph, the chairman of Universal. It was an unusual place, but it gave them a space to start creating their own institution. Before long they would fill the vacuum left by local government with an action group that worked for them. Downing Street, however, seemed to have other ideas.

Only a week before the disaster, Theresa May had squeaked back into Downing Street after losing the Conservative majority in a snap general election. Already shell-shocked by her own political catastrophe, she didn't show up at Grenfell until two days after the fire, and when she did, was accused of lacking empathy. As she was driven away in her convoy, escorted by police, local residents called her a coward.

Instead of engaging with Grenfell United, the government did something rather strange. Eleven days after the fire, officials introduced some of the GU committee to a local Sudanese community leader, Ibrahim El-Nour, whose aunt, it was understood, had perished in the fire. He had plans for his own representative group, the Grenfell Bereaved and Survivors' Trust, and had the founding paperwork ready to go.

"[The officials] were trying to say it would be easier, instead of having two organisations to talk to, [to] just have one," Sadafi said. "I remember Oliver saying: 'What do you mean, it's easier for you? It should be easier for the community."

The GU committee declined to sign up, and noted in their minutes the next day that the government officials were trying to "cherry-pick residents" and "showed complete ineptitude".

One of the officials persisted, emailing El-Nour and Sadafi to complain that they were not forming "a unified and truly representative group". She told them she would send cars the next day to bring them to meet the leaders of Gold Command, the government's Grenfell response group, adding: "This invite is only for you both." It looked like an attempt to divide and rule. The idea of being whisked off to government offices deepened Sadafi's suspicions and he refused.

The government persisted by calling a public meeting, and leafleted survivors promising that the trust would provide "full OWNERSHIP of all current and future issues relating to the Victims and Survivors of Grenfell".

Shahin Sadafi. Photograph: Leon Neal/Getty ImagesThe meeting was a shambles. Chairs were arranged outside the Westway community centre under the noisy flyover, and before the meeting could even get going, El-Nour was challenged by a group including one of the GU committee members, Mahad Egal, who had lived on the fourth floor. They didn't believe El-Nour had any connection to the tower. He said his Auntie Fathia had died there. "They assumed I meant a blood relative," El-Nour recalled. "They were saying: 'What flat? What floor?"

El-Nour explained that Fathia was known as "auntie" as a term of respect, but they were not satisfied, and shouted that he was "speaking for the police and the government", and the meeting broke up in acrimony. El-Nour had neither lost a family member, nor was he a survivor. He took no further part in organising Grenfell groups. He said he was well intentioned. A government source said it had wanted to "see if different groups could work together for the benefit of the community". But the GU committee didn't like it.

"This was government trying to simplify things for themselves," said Sadafi. "That woke us up. We knew people weren't coming to help us, but that people might be trying to jeopardise us and dismantle what we are doing. I was afraid of the people who should have been helping me."

From that point, Sadafi resolved to pour himself into GU and became its first chairman. He worked 16-hour days, meeting lawyers about inquests and the inquiry, which had been announced but was yet to begin, keeping track of people scattered across the borough in hotels and working out how to co-ordinate volunteers. All the while, he was in deep distress. "I was ready to hurt myself, I was so angry," he said. "I'd be walking along seeing posters of [missing] kids I saw growing up and I was breaking down."

Ten days after the fire, Sadafi was driving through Kensington when he felt overwhelmed. He froze at a traffic light, as the memories came flooding in. Traffic backed up behind him as he bawled his eyes out.

In August 2017, two months after the fire, May agreed to meet in private around 100 survivors at the five-star Royal Garden Hotel near Kensington Palace. GU members seized the chance to tackle her on the issue of class. One told her: "If this happened on the posher side of the borough, money would not be an issue, emotions would not be an issue and you would totally relate to them." Another said: "We are quite dignified and quite civilised people, and there's nothing wrong with social housing."

Tenants complained about ineffective key workers, offers of new homes on worse tenancy terms, and a hotel that had refused a survivor meals. They demanded that the public inquiry examine the way RBKC treated tenants, and that the inquiry chairman, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, a retired 72-year-old appeal court judge, appoint a more representative panel to help him look into the culture of social housing.

"You have challenged me tonight," said May. "And that's fair." She promised there would be £74m to buy new homes, money for lawyers to represent survivors and"no cover up" at the public inquiry. Less than two months after the government's failed attempt to back a rival survivors' group, May also said GU was "one of the good things that has happened".

For all this time, Grenfell United had been operating without any public face. In December 2017, the six-month anniversary, four of its members, Shahin Sadafi, Natasha Elcock, Ahmed Elgwahary and Bellal El Guenuni spoke for the first time in public about their ordeals. The bereaved and survivors were wrestling with an ever-growing list of concerns. Rehousing was going so slowly that 105 households displaced by the disaster were preparing to spend Christmas in hotels. There were fears that the planned public inquiry would fail to grapple with issues such as the neglect of social housing tenants.

The venue for GU's first public appearance was committee room 14 of the House of Commons, a dark and ornately decorated chamber that was packed with senior MPs and ministers. From the dais, Elgwahary spoke. "My mum and my sister were poisoned by the smoke, they were burned and they were cremated," he said. "I had to listen to them suffer. I had to listen to them die. I had to watch the flat burn for a couple of days. If that is not torture, I don't know what is."

His simmering anger stunned the room. From that point on, GU took on a more campaigning zeal and moved from coping with trauma and abandonment to finding a public and political voice. Some of the committee gave up work to dedicate themselves to the task, others took leave and everyone worked into the evenings. The youngest member, Tiago Alves, 21, who escaped from the 13th floor, put his physics degree at Kings College London on hold. "I always had respect for authority, but since the fire, that has turned on his head," he said.

They secured direct access to the prime minister, Sajid Javid, then communities secretary, Alok Sharma, the housing minister, and his successors, Dominic Raab and Kit Malthouse. Elcock would rush from her supermarket job to meetings. On one occasion she was running late to meet a cabinet minister because she had to handle a shopper's complaint about stocks of a particular bottled water. But it was becoming a vocation. "It hasn't been a choice for me," Mussilhy said. "I have been put in these circumstances where something horrific has happened to me and my family, my neighbours, my friends' families. It became my life."

GU also decided that the purity of protest is not enough. They have chosen negotiation and relationship-building with politicians embroiled in the very system they believe contributed to the deaths of their neighbours and loved ones. It has not always been easy, but the regular meetings, WhatsApp groups and camaraderie of a joint enterprise has kept them going.

Karim Mussilhy. Photograph: Christian Sinibaldi/The Guardian"I know it sounds wrong, but from something so horrific, a group of people has come together, doing different things for the same outcome," Mussilhy said.

Ten months on, they felt they were making progress. At a Downing Street meeting with the prime minister in April 2018, they spelled out the need for people with expertise in social housing to preside over the public inquiry alongside Moore-Bick. They demanded that the bereaved and the survivors steer the future plans for a memorial on the site of the tower, and they felt May was coming to understand their seriousness and respect their diligent approach. By now, different parts of the committee had become experts in different issues – a kind of shadow cabinet. Elcock covered mental health, Elgwahary and Daffarn handled tenants' rights, while Alves and a couple of others looked at cladding and building regulations. GU had the ear of officials and ministers.

But the work was taking a personal toll. By summer 2018, Sadafi was struggling; he had submerged his grief and trauma in GU work and, a year on, needed to stand down to deal with it. Elcock, who had lived in the tower for 20 years, stepped up. She is streetwise and shrewd, and known locally as a strong parent. She has never been any kind of campaigner. "It has thrust us into a world none of us ever envisaged we would be in," she said. "It's given us a different outlook on how things have been done."

She has also committed herself to GU for the long run, at least until decisions are made over who, or which organisations, might face criminal charges, possibly for manslaughter or corporate manslaughter – which is not likely until 2023, after the public inquiry has finished its work.

"Every time I have a tea break, I'm checking emails or doing something [for GU]," she said. "It does become difficult to balance. There are days when it absolutely hits me like a ton of bricks. There are people who died in that building that drive me forward. A 12-year-old girl or a four-year-old. When I feel like I want to give it up, they come back to me."

With its elected committee and formal standing as a family association, Grenfell United was becoming established. In February 2018, it opened its own headquarters on the sixth floor of an office block tucked behind Kensington High Street. GU Space has since become a place for survivors and those bereaved to receive counselling, health support, and to simply be together. A couple of times a week, there is a homework club for the dozens of school-age survivors, many of whom suffer PTSD.

It is calm and welcoming, with mustard and grey sofas, an orchid on the kitchen window sill and shelves of children's books. Among them is The Knight and the Princess, about a boy and a girl who fall in love and live happily in a "beautiful, warm and cosy" flat until an "evil dragon, envious of their happiness, kidnaps them and takes them away". It is about Gloria Trevisan and Marco Gottardi, young Italian architects who died in the fire. Most Friday afternoons, a science teacher called Archie with pink hair and orange dungarees entertains children with fun experiments.

"It's a relaxed, open space to engage with other children, and for us to catch up with other bereaved peiople and survivors, and to see if we can assist each other, if we want to share," said Hisam Choucair as he waited while his children, eight-year-old Zahraa and six-year-old Muhammed, were entertained one Friday in May.

The fire killed Hisam's mother, sister, brother-in-law and three young nieces, Mierna, Fatima, and Zaynab. He has described what happened as "an atrocity" caused by the segregation of rich and poor. He is one of the large majority of Grenfell survivors who are members of GU, and it helps him cope.

Anne-Marie Murphy, whose brother Denis Murphy died in the fire, is among hundreds more bereaved members. "It has brought us together," she said. "The committee has shown incredible strength and determination in representing us all in the fight for change, especially when some of us haven't been mentally or physically strong enough."

The committee helps members with housing problems and money, communicates with them through WhatsApp, and liaises with the NHS and the council. But what drives the leadership of GU is achieving political change. They want the legacy of their loss to be that a similar atrocity never happens again.

The one-year anniversary in June 2018 was marked with a vigil at the base of the tower. The bereaved laid white roses, and a cleric from a local mosque sang Qur'anic verses in a haunting, pure voice that echoed around the shrouded tower block. In the following months, frustrations with the official response started to grow. At the public inquiry in September, the London fire commissioner, Dany Cotton, shocked survivors by saying she stood by the decision to tell people to stay in their flats well after the fire had raged out of control. Robert Black, the chief executive of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, admitted the emergency plan for the building was 15 years out of date. And across England, hundreds of tower blocks remained wrapped in combustible cladding, leading Daffarn to warn the media: "Grenfell Two is in the post."

Survivors still faced problems with their new homes. Many were still in hotels. In government, Javid had been replaced by James Brokenshire as the cabinet member in charge of Grenfell, and GU were getting to know their third housing minister since the fire. The public inquiry was grinding along slowly. The first phase concluded in December. Its report on what happened on the night of the fire, expected to contain recommendations for changes that could protect tens of thousands of other high-rise residents, was due in spring, but never came.

On the evening of 19 March 2019, Karim Mussihly walked out of the boardroom at GU Space and screamed in frustration. He had been in there since 11am, and would not finally leave until 9.30pm. The committee was struggling to get answers out of Mark Fisher, director general of the Grenfell public inquiry, about the next steps. The lack of answers was baffling. After all, who was the inquiry for?

Martin Moore-Bick, chair of the Grenfell Tower inquiry (left), and Mark Fisher, its director general. Photograph: Henry Nicholls/ReutersAfter Fisher was shown out, the meeting rolled through a crowded landscape of other concerns: people sleeping in buildings with dangerous cladding; poor handling of traumatised Grenfell children by schools; a foul-up by officials planning a permanent memorial on the site of the building; and the detailed work of utility bills and welfare payments for the bereaved and survivors.

Elcock rubbed her face with fatigue and frustration. "[We] need to book Brokenshire in a month from now," she said.

Brokenshire, a somewhat bland former corporate lawyer, was now key to achieving the change GU wanted to see. But progress seemed to be slowing. Brexit was too often blamed. The mood was hardening. Ministers and officials were "taking our kindness for weakness", Mussihly said.

Six weeks later, the meeting with Brokenshire was finally fixed. The GU team arrived at the Palace of Westminster and found a crumbling democratic institution. A protester screamed "Stop Brexit" through the railings, a mouse darted across the stone floor of the parliament cafe and water stains ran down the walls leading to committee room 18, where Brokenshire waited. After polite greetings, the meeting settled into a pattern – the bereaved and survivors took turns to tear strips off the secretary of state for the lack of progress, while Brokenshire's responses filled time but gave little away.

Finally, it got too much to bear. Elcock told him that, since the GU team are not professionals, they have to beg, borrow and steal time from family and work to come to these meetings. The lack of progress "is beyond frustrating," she said. "It is incompetence or it is indifference."

When Ed Daffarn was battling with Grenfell Tower's council landlords before the fire, he had been frustrated by their failure to take effective action, or to listen to tenants' fears. Two years down the line, the ministers in charge of finding housing for survivors and steering the inquiry seemed to be showing the same incompetence. In May, Brokenshire finally allocated £200m to fix dangerous cladding on private towers, having already allocated £400m to social housing.

But tens of thousands of leaseholders and tenants were still living in properties covered in combustible cladding. The inquiry's first-phase report, detailing what happened on the night of the fire, was delayed until October 2019, and the second phase of the inquiry, examining the refurbishment, will not start until 2020. Social-housing reforms remain in draft form. As momentum has stalled, the emotional toll on the GU members has risen.

"I go to my counselling and say I can handle it if we get the change," Daffarn said. "If we don't get the change, I don't know what I am going to do. I feel like I'll need to leave the country. This is deeply personal for every one of us. From the minute I wake up until I go to bed at night, I pretty much don't think of anything else apart from trying to get that change."

The GU committee has been propelled to the frontline of battles against social inequality and racial prejudice. Mussihly, who has not been able to find work since becoming a public face of GU, has received nasty abuse on Facebook. One post, alluding to his white wife, read: "Take your muzzy-loving wife and get out of the country. Your families deserved to die in falafel tower."

They also had to watch as a group of bonfire party revellers in south-east London shared a video of a burning effigy of Grenfell Tower with cardboard cut-out residents at the windows. A man has pleaded not guilty to sharing a grossly offensive video and goes on trial next month.

A more subtle gulf also persists between the Grenfell families and those in power. Elcock, for one, clearly finds Nick Hurd, the minister for Grenfell survivors, irritating. Hurd, the son of the former foreign secretary Douglas Hurd and educated at Eton and Oxford, has a patrician bearing. On a visit to parliament in April to meet ministers, Elcock sarcastically asked one of his officials: "Where's Lord Hurd today? Doing some work, is he? That's nice of him."

When the GU delegation met Hurd later, he was with Kit Malthouse, the housing minister. They had come from the Commons debate about who should pay to fix hundreds of private towers fitted with combustible, Grenfell-style cladding. The government had avoided answering, but the ministers now seemed to be trying to adopt a pally posture with GU: feet spread and hands in pockets like golfers at the 19th hole.

"If something else happens tonight, who is going to be responsible for that?" asked Mussihly.

As the ministers shuffled and looked down at their shoes, there was an echo of the pre-fire gulf between RBKC and its tenants: white, middle-aged, public school-educated Conservatives stonewalling the concerns of working-class men and women with heritage from Morocco to Colombia. When it was time to go, Hurd offered handshakes with his face arranged in an expression of sympathy, but Elcock pulled him towards her and refused to let go.

"I am still waiting for your email from three weeks ago," she said quietly. "In an ideal world, I would have one by close of play tomorrow."

Hurd nodded, looking chastened.

Outside the gates of Parliament, frustration spilled over. Elgwahary said: "Our families were burned and you have to remind them we are not a normal group. You have to do that to sensitise them."

Coming up to the two-year anniversary, Daffarn is now among those considering a change in strategy. He reckons he has had more than 30 meetings with ministers and civil servants, and knows not enough has been achieved. This spring, he received back a few possessions from his beloved flat: a diary, part of a coffee set his mother left him, and a fridge magnet "completely burned to shit".

"You have to make something good come out of something bad, and what is so terrifying about this is I am beginning to doubt whether that's going to happen," he said. "There's an empathy gap, but they also have this problem that they are indifferent and incompetent. We had every right to shout at people and be upset. We haven't done any of that. We have gone in and negotiated. We have worked. We have been grown-up about it."

He said they are considering a different posture. Such was the violence they suffered during the fire, the idea that more violence could help is anathema: GU has been committed to a peaceful, constructive and pragmatic approach. But, in frustration, perhaps, Daffarn now says: "The one thing they fear is social unrest – and rightly so. Go to any meeting in Kensington and that anger is still there. It hasn't dissipated. We wasted 22 months trying to do it this way, and now we have to come up with another solution. We have learned a lot. They failed us."

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, and sign up to the long read weekly email here.

• This article was amended on 11 June 2019 to correct an earlier version which misdescribed Francis O'Connor as a Grenfell resident.

Disclaimer:Everyone posting to this Forum bears the sole responsibility for any legal consequences of his or her postings, and hence statements and facts must be presented responsibly. Your continued membership signifies that you agree to this disclaimer and pledge to abide by our Rules and Guidelines.To unsubscribe from this group, send email to: ugandans-at-heart+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com

---

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "Ugandans at Heart (UAH) Community" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to ugandans-at-heart+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/ugandans-at-heart/CAMs%3D6-z6-SV8syzRCk9FiityJpcSgVZxsDpAR1d_NqMPz_xAxg%40mail.gmail.com.

0 comments:

Post a Comment