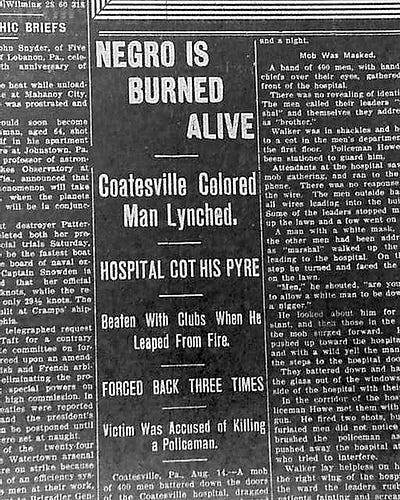

{UAH} The forgotten lynching of Zachariah Walker was one of our most shameful — and it was in the North

The forgotten lynching of Zachariah Walker was one of our most shameful — and it was in the North

In a small Pennsylvania town, he was burned alive

Zachariah Walker screamed before the mob threw him into the fire. Walker, a black iron worker from the South, was already bloodied from a recent surgery that removed a bullet from his jaw, and was agonized by the experience of being dragged hundreds of feet from his hospital bed to a field where a fire had been built by a white mob. "For God's sake, give a man a chance!" Walker yelled. It did not matter. They threw him in.

The lynching of Zachariah Walker happened in the bustling steel town of Coatesville, Pennsylvania, on the night of August 13th, 1911. At the time, Coatesville was enjoying newfound prosperity. The steel mills were booming, and to meet growing production demands, they needed workers.

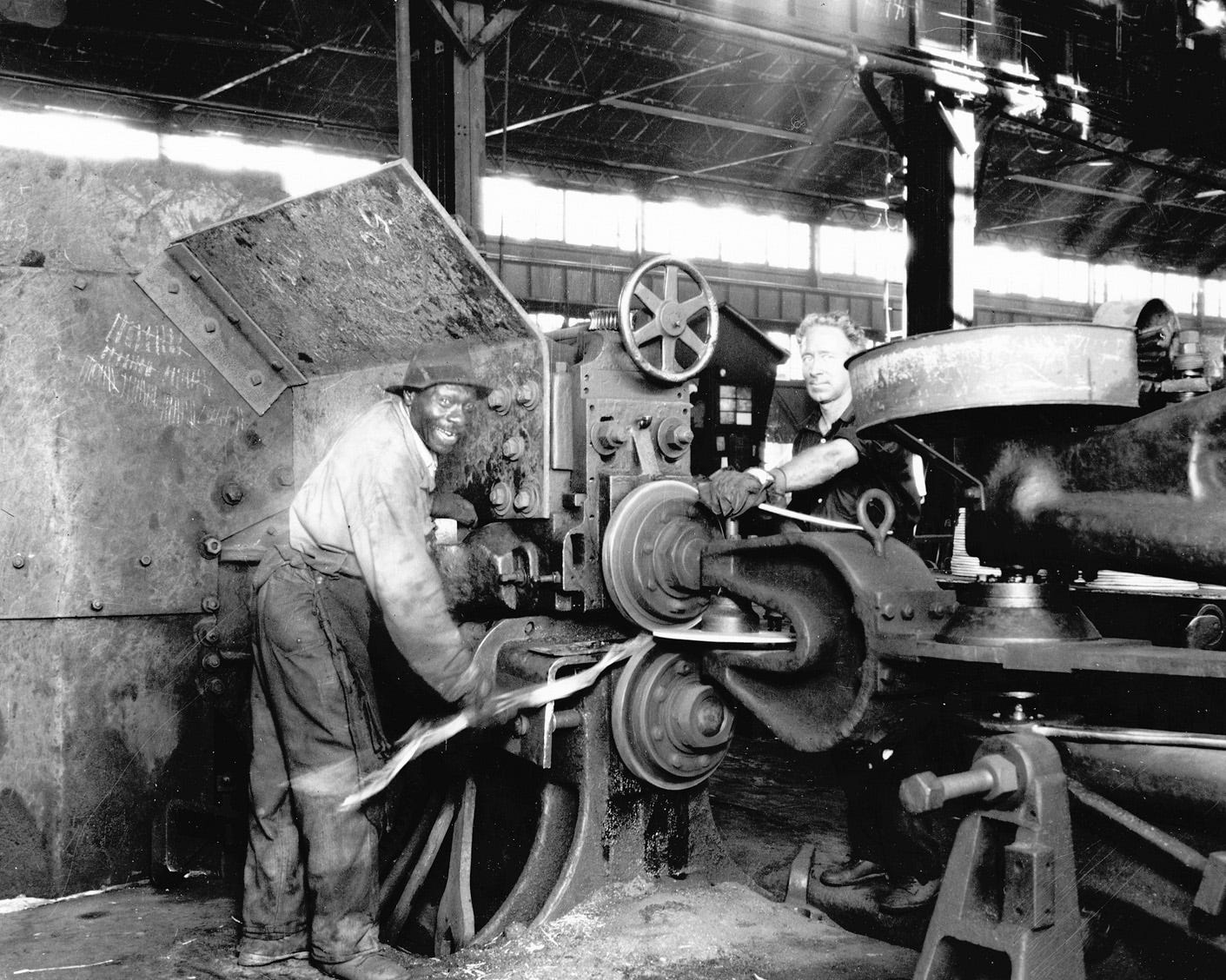

For the most part, this need was filled by European immigrants and blacks from the South. Walker, a lever-puller for the Worth Brothers Steel Company, left his wife and children behind in Virginia for the new position. He settled in a town of shacks on a bluff overlooking Coatesville proper, where he lived alongside other black and immigrant laborers.

The new influx of workers signified to Coatesville a growing prosperity, but it also coincided with a perceived loss of social and communal harmony. The borough of 11,000 fixated on its demographic shifts (an 87 percent native white population decreased to 73 percent in a decade), and increasing instances of crime, gambling, drunkenness, concealed firearms, and fighting disturbed residents.

Residents of Coatesville grew especially weary of pay weekends, when relieved mill workers became intoxicated revelers. These workers blew off steam in even less savory ways, clogging up Main Street and stressing the town's six-man police force.

On Saturday, August 12, a somewhat drunken Zachariah Walker was crossing a bridge on the way home when he saw two Polish workers. Walker, confessing he was "feeling pretty good," decided on a wicked idea of a prank. He took out his revolver from his person, and fired two shots over their heads. They ran away in terror.

Edgar Rice was working security for the mill that night when he heard the gunshots. He was beloved in Coatesville. An affable, portly man, he was known for his compassionate patrolling, often escorting drunk workers home, rather than having them arrested.

Rice confronted the drunken Walker, who would later recall getting "a little sassy." Eventually Rice grew tired of the hassle and told him, "If you don't come with me, I will hit you over the head with this club."

A tussle, then a panic ensued. Walker soon believed the fight was escalating to lethal ends. Rice took out his revolver, as did Walker, who shot the police officer two or three times and fled the scene. In a few hours, Edgar Rice was dead.

Walker went on the run. Though no one saw the incident unfold, the two Poles provided a link to the culprit. Search parties looked all through the night, when the next morning a boy on his way to collect eggs saw Walker in a barn.

Two men were notified and they confronted Walker. They were unarmed, and Walker struck one down with a blow. He took his revolver out and pressed it to his chest, pulling the trigger. Luckily for the man the gun had jammed. Walker ran on.

A sheriff's posse finally found Walker in the woods, where he was hiding in a cherry tree. The searchers pointed their guns at Walker, who, knowing his fate, decided to end his life himself. Walker raised his revolver to his temple and fired. He missed, the bullet going from his ear to his jaw. He fell to the foot of the tree. His suicide attempt failed. He was injured and unconscious, but alive.

Walker was brought to jail, and the crowd who gathered outside was told the menace had died in an effort to get them to disperse. With Walker in custody, the police chief and other high ranking officials collected his confession. The chief of police would later convey the confession to the public, claiming Walker was "proud" of what he'd done, omitting that he claimed he acted in self-defense.

Walker was then brought to a hospital to remove the bullet from his face. To keep him from attempting suicide or an escape, Walker's right ankle was handcuffed to the iron-frame bed, and he was placed in a canvas straight jacket, buckled to the four corners of the bed.

Meanwhile, a crowd of teenagers and young men gathered on Main Street. Two officials who recently left the hospital told them that with only one person on duty, it would be easy to abduct Walker. After a while talking and gathering, the crowd was provoked by the rumor that an ambulance was soon to carry Walker to a hospital in West Chester, as well as a teenager's speech which reiterated the meager resistance awaiting them. Galvanized by a thirst for revenge, as many as 2,000 people marched shoulder to shoulder along Main Street to the hospital.

After small opposition from the officer camped inside Coatesville Hospital, the mob broke in. Many wore rags or handkerchiefs over their face, which would later impede witness testimony. Mobsters grabbed Walker, soon finding him fastened to the bed. They needed a way around the handcuffs. They beat him and undid the straight jacket, eventually resolving to detach the iron footboard from the bed, to which his right ankle was attached. They dragged him away through the hospital corridor, onto to the porch that sat below a pediment and white columns.

The mob of hundreds cheered, yelling "Shoot him!" "Kill him!" "Hang him!"

The crowd resolved to burn him. They dragged the maimed and beaten Walker down a dirt road to a field. "I killed Rice in self-defense," Walker yelled. "Don't give me no crooked death because I'm not white."

He was thrown into the fire nevertheless. It seared his flesh, and with it charred he escaped from the pyre. The crowd, stunned at his resilience, beat him with rails from a broken fence and thrust him back in, adding fuel to box him in as he burned.

Yet Walker escaped a second time. The crowd met this new effort with sadistic joy as a coda to a long night of a criminal's suffering. They beat him with rails again as his burnt flesh hung from his body, the scent of which made the air grow acrid. Two men held a rope on both sides around his neck and pitched him into the fire one last time. Walker's screams were heard over a half-mile away. The crowd huddled around him in the firelight until Zachariah Walker left behind a charred figure that was no longer him.

As was common with lynchings, members of the mob descended on the scene to collect souvenirs, including the handcuffs. One boy was said to have kept a finger in his pants pocket for six weeks. Paperboys sold souvenirs along with news of the murder. The next day, Walker's gruesome remains were photographed in a wooden shoebox, filling it not even halfway.

Said Edgar Rice's widow —a mother of four who stayed away from the scene at the insistence of those consoling her — of the vengeful killing: "I wanted to apply the match, I wanted to see him burn."

Fifteen people were indicted for their role in the lynching, including two police officers. The story and ensuing trial became national news. At the time, the sheer fact of an American lynching was not unusual. Indeed, the very same day Walker was lynched, a man named John Lee was burned and hanged in the town of Durant, Oklahoma. But Walker's death happened in the North.

In the end, Coatesville residents stayed mum, and all fifteen were acquitted. Walker would become the eighth and final person lynched in Pennsylvania.

Even former President Theodore Roosevelt was stunned, writing an editorial in The Outlook describing the lynching as "revolting to the last degree" and "a horrible wrong for which the whole country must bear the responsibility."

The NAACP sent William Sinclair, one of the organization's founders and a former slave, to quietly sit in on the trials and send reports back to the offices in New York. The association's magazine, The Crisis, wrote that "the Coatesville horror is the subject of wide comment and more whole-souled denunciation than has often greeted outrages against the Negro." The piece quoted a series of strong editorials, many of which argued that North and South did not matter. The violence seen in that Pennsylvania field was a "national extremity of community crime and a broadly national shame."

But W.E.B. DuBois was less optimistic about the widespread denunciation. "The last lyncher is acquitted," he wrote bitterly, "and the best traditions of Anglo-Saxon civilization are safe."

Even so, the NAACP opened three branches in Pennsylvania as a result.

On the first anniversary of the lynching, the writer John Jay Chapman held a prayer memorial. No more than half a dozen people showed up (perhaps as few as two were there), but his speech was later serialized, in places ranging from the Coatesville Record to Harper's Weekly.

"I understand that an attempt to prosecute the chief criminals has been made, and has entirely failed," he said, "because the whole community, and in a sense our whole people, are really involved in the guilt….A nation cannot practice a course of inhuman crime for three hundred years and then suddenly throw off the effects of it."

--

Disclaimer:Everyone posting to this Forum bears the sole responsibility for any legal consequences of his or her postings, and hence statements and facts must be presented responsibly. Your continued membership signifies that you agree to this disclaimer and pledge to abide by our Rules and Guidelines.To unsubscribe from this group, send email to: ugandans-at-heart+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment